Bangladesh stands at a delicate intersection of opportunity and caution. Japan’s proposal to conclude a Defence Cooperation Agreement (DCA) with Dhaka has opened the door to a new kind of partnership — one based not on alignment, but on capability and trust. If pursued wisely, it could quietly transform Bangladesh’s defence posture for the next generation.

A Shift in Strategic Thinking

The offer from Tokyo comes at a time when Bangladesh’s defence modernisation is entering a more mature phase. Forces Goal 2030 has already guided the military beyond its post-1971 rebuilding logic toward a doctrine of sustainability, technological independence, and professionalisation.

In this context, Japan represents something different: a partner that values precision, maintenance, and reliability over quantity. Unlike many of Bangladesh’s traditional suppliers, Japan offers a model that focuses on systems integration, training excellence, and institutional discipline. These are exactly the areas where Dhaka seeks enduring progress.

A DCA would give the Bangladesh Armed Forces access to Japan’s world-class expertise in logistics, maritime engineering, maintenance systems, and information technology. It would also formalise regular staff talks, joint exercises, and officer exchanges — tools that build competence, not dependency.

“Unlike traditional suppliers, Japan offers a model built on discipline, systems integration, and professional trust.”

The Benefits Beyond Weapons

For Bangladesh, the potential dividends go far beyond procurement. Japan’s shipbuilding experience and coastal surveillance technology could boost both the Navy and Coast Guard’s ability to protect maritime trade routes, combat illegal fishing, and respond to disasters.

Tokyo’s Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology allow for carefully controlled exports of non-lethal or dual-use systems. That means Bangladesh could gain access to high-end sensors, communications equipment, and C4ISR platforms — capabilities that strengthen deterrence without provoking regional anxieties.

Most importantly, such cooperation would bring the kind of structured, standards-driven training Japan is known for. Bangladesh’s officers and engineers could learn from a military that prizes efficiency, accountability, and precision — values that translate directly into operational readiness.

What It Won’t Bring

However, this agreement will not turn Bangladesh into a Japanese arms customer overnight. Japan’s pacifist constitution still restricts lethal weapons exports. Any transfer of offensive systems — missiles, fighters, or submarines — would require Cabinet-level approval in Tokyo and compliance with strict oversight.

This means Bangladesh’s near-term gains will come through knowledge, training, and maintenance — not through the acquisition of combat platforms. And that is no bad thing. These are the building blocks of a sustainable defence force.

The other limitation is financial. Japanese equipment and industrial cooperation are high-quality but expensive. To make this partnership worthwhile, Bangladesh must negotiate meaningful technology transfer and local participation. Without those, the cost-benefit ratio could tilt unfavourably.

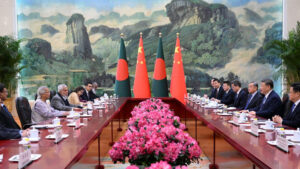

China Will Be Watching

Any new defence partnership in South Asia inevitably carries a geopolitical echo. China — Bangladesh’s largest defence supplier — will observe the Japan DCA with close attention.

Beijing is unlikely to react with hostility, but it will interpret the move as Dhaka diversifying away from its traditional comfort zone. In response, China may offer improved terms on future defence or infrastructure projects, expedite pending deliveries, or intensify diplomatic engagement.

In short, Bangladesh should expect a competitive response, not confrontation. Beijing understands Dhaka’s desire for diversification, but it will act to preserve influence.

The key for Bangladesh is careful messaging: presenting the DCA as an initiative focused on capacity building, maritime safety, and technology development — not a political alignment within the Indo-Pacific framework.

“Framed as capability-building, the Japan DCA strengthens Bangladesh’s independence — not its alliances.”

Strategic Autonomy, Not Alignment

The deeper significance of this agreement lies in what it represents for Bangladesh’s evolving identity as a middle power. Strategic autonomy today is not about isolation — it is about choice.

Bangladesh has already proven adept at maintaining balanced relations with China, India, the United States, Türkiye, and South Korea. A partnership with Japan would simply add another layer of resilience and bargaining power.

By cultivating multiple partners, Dhaka avoids overreliance on any single supplier or political bloc. It keeps options open — a principle that lies at the heart of effective defence diplomacy.

The Smart Path Forward

To make the most of the Japan DCA, Dhaka should pursue a phased and practical agenda:

- Start with training, maintenance, and shipyard cooperation.

- Embed technology transfer and industrial participation clauses in every contract.

- Frame the partnership around maritime safety and humanitarian response, avoiding the optics of alliance-building.

- Continue procurement diversification — balancing China’s hardware, Türkiye’s innovation, and Japan’s precision.

This layered approach will allow Bangladesh to strengthen its forces while preserving its strategic independence.

A Quiet Step Toward a Stronger Future

If managed with foresight, the Bangladesh–Japan Defence Cooperation Agreement could become one of Dhaka’s most consequential strategic achievements in recent years. It aligns with Bangladesh’s defence philosophy — peace through preparedness, capability through cooperation, and sovereignty through balance.

This is not a shift of allegiance. It is a maturation of statecraft.

Because in a world where great powers compete for influence, Bangladesh’s strength will lie not in taking sides — but in standing firm on its own.

Ayesha Farid is a regional security specialist focusing on South Asia, with over a decade of experience analysing inter-state tensions, cross-border insurgency, and regional power dynamics. She has worked with leading policy think tanks and academic institutions, offering nuanced insights into the complex security challenges shaping the subcontinent. Ayesha’s expertise spans military doctrines, border disputes, and regional cooperation frameworks, making her a vital contributor to BDMilitary’s coverage of South Asian strategic affairs. She leads the Geopolitics & Diplomacy section at BDMilitary. Ayesha holds a dual master’s degree — a Master in International Relations from the IE School of Politics, Economics & Global Affairs, Spain, and a Master of Public Policy from the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, Canada — combining deep academic insight with practical policy expertise.